Clam Consternation

Everyone comments on how many rubber gloves wash up on Waikawa Beach. There's a strong suspicion amongst locals that the gloves and frequent large swathes of dead shellfish are connected with the clam dredge that comes through quite often.

The dredge is harvesting surf clams that live up to 10 metres deep in the sea bed. It uses a technique that pumps water into the seabed and then takes the shellfish on board where they are sorted and saved in water for later processing.

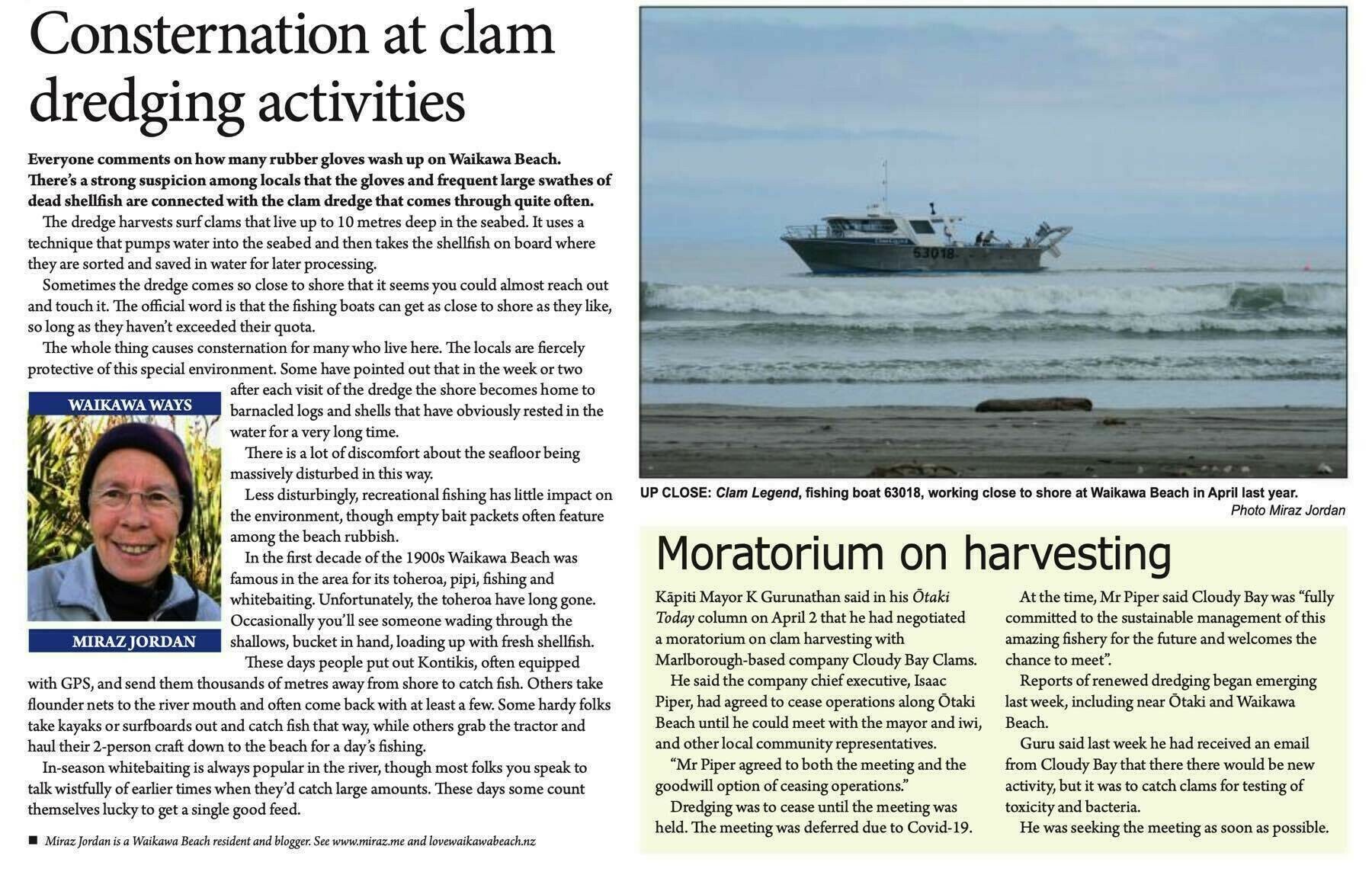

Sometimes the dredge comes so close to shore that it seems you could almost reach out and touch it. The official word is that the fishing boats can get as close to shore as they like, so long as they haven't exceeded their quota.

The whole thing causes consternation for many who live here. The locals are fiercely protective of this special environment. Some have pointed out that in the week or two after each visit of the dredge the shore becomes home to barnacled logs and shells that have obviously rested in the water for a very long time.

There is a lot of discomfort about the seafloor being massively disturbed in this way.

Less disturbingly, recreational fishing has little impact on the environment, though empty bait packets often feature among the beach rubbish.

In the first decade of the 1900s Waikawa Beach was famous in the area for its toheroa, pipi, fishing and whitebaiting. Unfortunately, the toheroa have long gone. Occasionally you'll see someone wading through the shallows, bucket in hand, loading up with fresh shellfish.

These days people put out Kontikis, often equipped with GPS, and send them thousands of metres away from shore to catch fish. Others take flounder nets to the river mouth and often come back with at least a few. Some hardy folks take kayaks or surfboards out and catch fish that way, while others grab the tractor and haul their 2-person craft down to the beach for a day's fishing.

In-season whitebaiting is always popular in the river, though most folks you speak to talk wistfully of earlier times when they'd catch large amounts. These days some count themselves lucky to get a single good feed.

Originally published in Ōtaki Today, May 2020, page 19.